IMPERIALISM AND THE BIBLE: Archaeology and Power crafting a Holy Land

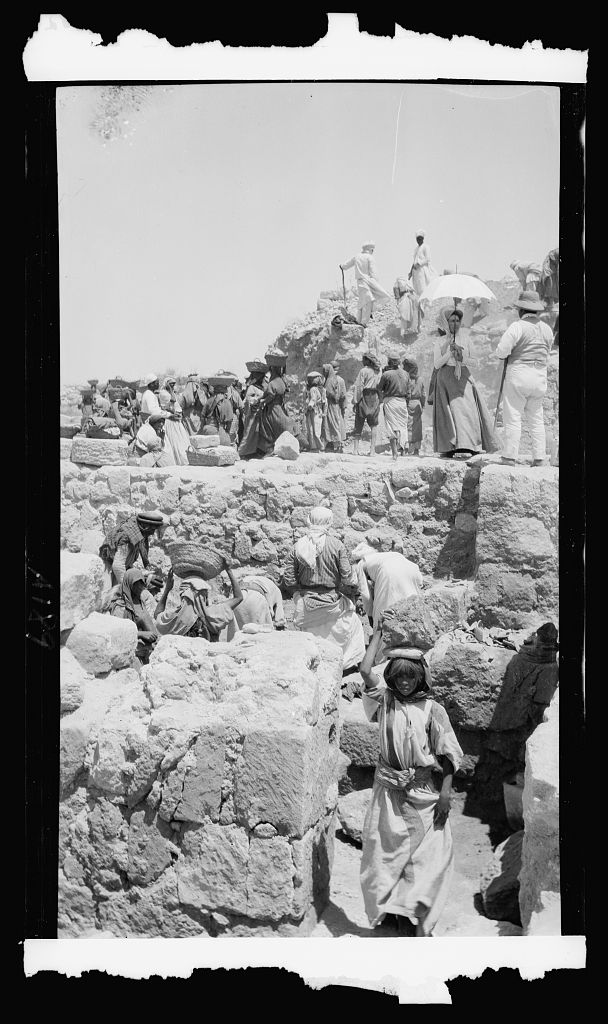

Women as archaeological labour. Matson Collection, Library of Congress

Archaeology to appropriate the past of Others

In the mid- and late 1800s, the European Imperial powers competed to extend their respective sphere of influence over the territories ruled by a declining Ottoman Empire, infiltrating its structures under the pretext of assistance (Liverani 2005). One of the instruments in this competition was the creation of foreign schools of archaeology, which acted more often as a hub for foreign archaeologists rather than as training facilities for native professionals, furthering and perpetuating the existent unequal power relationship (Díaz-Andreu 2007). Only in Palestine, foreign national schools of archaeological research mushroomed in the early 20th century, like the Ecole Biblique et Archeologique Française (1890), the Deutsches Evangelisches Institut für Altertumwissenschaft des Heiligen Landes (1900), the American School of Archaeological Research (1900), and the British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem (BSAJ, 1919).

As Mario Liverani noted, the ancient past of the Middle East was not only studied, but more fundamentally appropriated, incorporated into a grand narration of the origins of Imperial Western Power: rising from Mesopotamia, and transferred to Egypt, Assyria, Media, Persia, the Greeks and congealed into the Roman Empire (Liverani 2005). As far as the trasmission of Imperial power from the Roman Empire to modern, Western Europe, the gap was filled by Biblical archaeology, which has a primary geographic focus on Palestine.

Biblical archaeology, reinforced the Western Imperial appropriation of the past of the Middle East by depriving Palestinian past of its autonomy, and incorporating it into the historical arc of the West through a religious lens, characterising Imperial power as being transferred from Rome to Middle Ages Europe and finally to the Modern European world through Christianity (see: Whitelam 1996; Silberman 1998; Finkelstein and Silberman 2001; Silberman 2004; Liverani 2005; Hjelm and Thompson 2016).

Archaeology in the Middle East and Palestine, as Margarita Díaz-Andreu (2007) writes, was an appropriative effort of “consolidation of the mythical roots of the West”.

Imperial appropriation of the past was not only narrative, but was also practical: archaeological research amounted, at times, to a real pillage of the material heritage of the countries under the foot of imperial domination. The transfer of artefacts from the field to warehouses and museum of the countries of origin of the excavators was common practice, and they have thus become the bulk of the material on exhibit in the national museums of former imperial powers. Other artefacts, considered of lesser academic relevance, or hailing from places excluded from the mythical history of imperial power such as Africa, Central Asia and India, were funnelled into the westerns arts market to enrich private collections (Díaz-Andreu 2007).

The bible, the shovel and the gun.

Archaeologists did not come to Palestine alone, armed only with a shovel and a Bible. For the most part, Imperial powers deployed them alongside cartographers and military attachés. The British Palestine Exploration, founded in 1865, launched a reconnaissance survey of Palestine that was undertaken in liaison with the British War Office from 1871 to 1897, and served to produce maps that could facilitate the movement of British troops in case of conflict. Palestine, however, was not a terra incognita: it was already previously known through the narrations of the Bible and the Gospels. Therefore, biblical archaeologists were deployed to Palestine together with cartographers and military offices, to “retrieve” on the ground the traced of the geography of the scriptures. As a result, Arab Ottoman Palestine disappeared from the maps; Palestine was “mapped back” onto the past that the Biblical narration described (Abu el-Haj 2001).

Through this highly politicised and militarised process of mapping and excavation, Palestinian Tell Sebastia was transformed into Israelite Samaria.

What did Imperialism at work look like?

Imperial digs were usually grand-scale projects that were led by a small number of Western archaeologists, and physically conducted by a large number of local women, men and children. Under the supervision of the scholars, the local labourers dug, filled baskets with earth, transported them to the sieves to search for small artefacts and relevant fragments, and then moved the remainder of dirt to landfill.

The narration of these grand works reached us through the words of the Western excavators, who kept diaries to record the progress of excavation and reported in publication details about the organisation of the workforce. As typical of that day and age, the descriptions made often use of racist language and stereotypes. For example, Georde Reisner, Clarence Fisher and David Gordon (1924) write about the workforce of the first expedition (Harvard expedition of 1908-1910):

“The local workers were drawn mainly from Sebaste (…) They showed some inclination to take advantage of their position as landowners; but a few cases of fines and dismissals checked this tendency. The village of Burka, notorious as a wild, lawless place, came next in numbers, and furnished a greater proportion of satisfactory workers than any other. The other villages from which we drew were Belt Imrin, Nusf Jebil, Jennesinia, Nakurah, and Deir Shuraf. These people, especially the men, were at the beginning undisciplined, inexperienced, and indolent. It was our task to build up out of this mob an organized body of disciplined, industrious, and skilful workmen (…) the very first requirement was to obtain a hold on the workpeople. After long consideration, I fixed on a scale of wages which made our service the most desirable employment in the country. Men employed in excavating, Class I, were paid 11 piastres (Nablus) a day; Class II, 10 piastres. Women, carriers, Class I, were paid 9 piastres; Class II, 8 piastres. Children, Class I, were paid 7 piastres; Class II, 6 piastres. I The effect of this scale was to give us the pick of a great number of workpeople, so that we could have had several thousand at any time, and to make each workman extremely anxious to keep his job.”

The relationship between local people and foreign archaeologists were not always smooth. Much to the contrary: local landowners had their legitimate concerns about the sequestration of their farmlands, and demanded reassurance and compensation through alternative labour, in the face of which they were regularly blackmailed with fines and dismissals. The inequitable relation of power between the Imperial archaeologists and the local landowners and labourers was complicated also by the role of local negotiators. These people tried often to take advantage of their position of relative power: for example, during the campaign of 1931-1935, the so-called Joint Expedition, one especially unpleasant incident involving the local head of village, or mukhtar, happened. Dame Kathleen Kenyon participated in that campaign in affiliation with the British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem and reported it in a letter to her mother. Her biographer Miriam Davis (2008) recounts it as follows:

“By the end of the final season John Crowfoot reported that he had signed 150 agreements concerning fees, including payments for rent, wages, and the hire of various relatives. (…) On one occasion work was held up because the owners of some of the land that needed to be leased demanded to be hired permanently by the excavation. The headman, or muktar[sic.] of Sebastia suggested to Crowfoot that he agree to the landowners’ terms. Later he explained that he meant that they should be hired, the agreement regarding the land signed, and the landowners sacked the next day. K(athleen), (…) approved of these tactics, telling her mother that the muktar “is a wonderful man!”.”

In the previous Imperialist campaign as well, the local commissioner reportedly tried to divert the compensations for olive tree damage and land use loss from the local landowners to some unspecified “leaders” in Nablus, as Reisner noted in his diaries. However, amongst his dismissive remarks about the commissioner Hasan al-Husseini, Reisner mentions that he had organised a 21-day workers strike, appointed a local supervisor who would have “spoilt” the workforce, and insisted that all the artefacts be stored in local facilities and that even the American field director should obtain permission to access them (in Tappy 2016).

Maybe, in hindsight, al-Husseini was merely trying to bring the balance of power, so structurally skewed towards the emissaries of Western Imperialist archaeology, back towards the Palestinians.

Read more

Abu El-Haj, N. (2002) Facts on the ground: Archaeological practice and territorial self-fashioning in Israeli society. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.Davis, M.C. (2008) Dame Kathleen Kenyon: Digging up the holy land. United States: Left Coast Press.

Diaz-Andreu, M. (2007) A world history of nineteenth-century archaeology: Nationalism, colonialism, and the past. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hjelm, I. and Thompson, T.L. (eds.) (2016) History, archaeology and the bible Forty years after ‘historicity’: 6: Changing perspectives. Devon, United Kingdom: Routledge.

Liverani, M. (2005) ‘Imperialism’, in Pollock, S. and Bernbeck, R. (eds.) Archaeologies of the Middle East. Critical perspectives. Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 223–243.

Reisner, G. A., Fisher, C. S., & Lyon, D. G. (1924). Harvard excavations at Samaria. 1908-1910. Harvard University Press.

Silberman, N.A. (1998) ‘Whose game is it anyway? The political and social transformation of American Biblical Archaeology’, in Meskell, L. (ed.) Archaeology Under Fire. Nationalism, politics and heritage in the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East. London: Taylor & Francis, pp. 175–188.

Silberman, N.A. (2004) Digging for god and country: Exploration, Archaeology, and the secret struggle for the holy land, 1799-1917 [1982]. New York: Distributed by Random House.

Tappy, R. (2016) “The Harvard Expedition to Samaria: A Story of Twists and Turns in the Opening Season of 1908,” Buried History: Journal of the Australian Institute of Archaeology 52: 3-30.

Whitelam, K.W. (1996) Invention of ancient Israel. New York: Routledge.